Lets Write a Compiler!

Our goal is to write a compiler which is a function:

compiler :: SourceProgram -> TargetProgramIn 131 TargetProgram is going to be a binary executable.

Lets write our first Compilers

SourceProgram will be a sequence of four tiny “languages”

- Numbers

- e.g.

7,12,42…

- Numbers + Increment

- e.g.

add1(7),add1(add1(12)), …

- Numbers + Increment + Decrement

- e.g.

add1(7),add1(add1(12)),sub1(add1(42))

- Numbers + Increment + Decrement + Local Variables

- e.g.

let x = add1(7), y = add1(x) in add1(y)

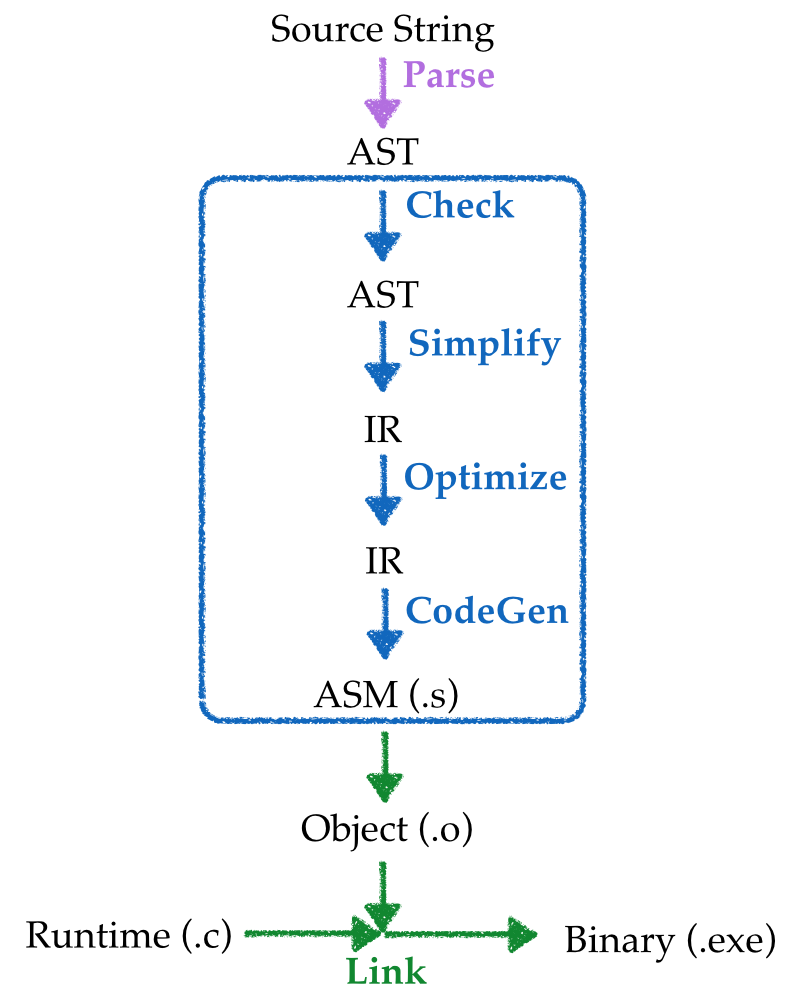

Recall: What does a Compiler look like?

An input source program is converted to an executable binary in many stages:

- Parsed into a data structure called an Abstract Syntax Tree

- Checked to make sure code is well-formed (and well-typed)

- Simplified into some convenient Intermediate Representation

- Optimized into (equivalent) but faster program

- Generated into assembly

x86 - Linked against a run-time (usually written in C)

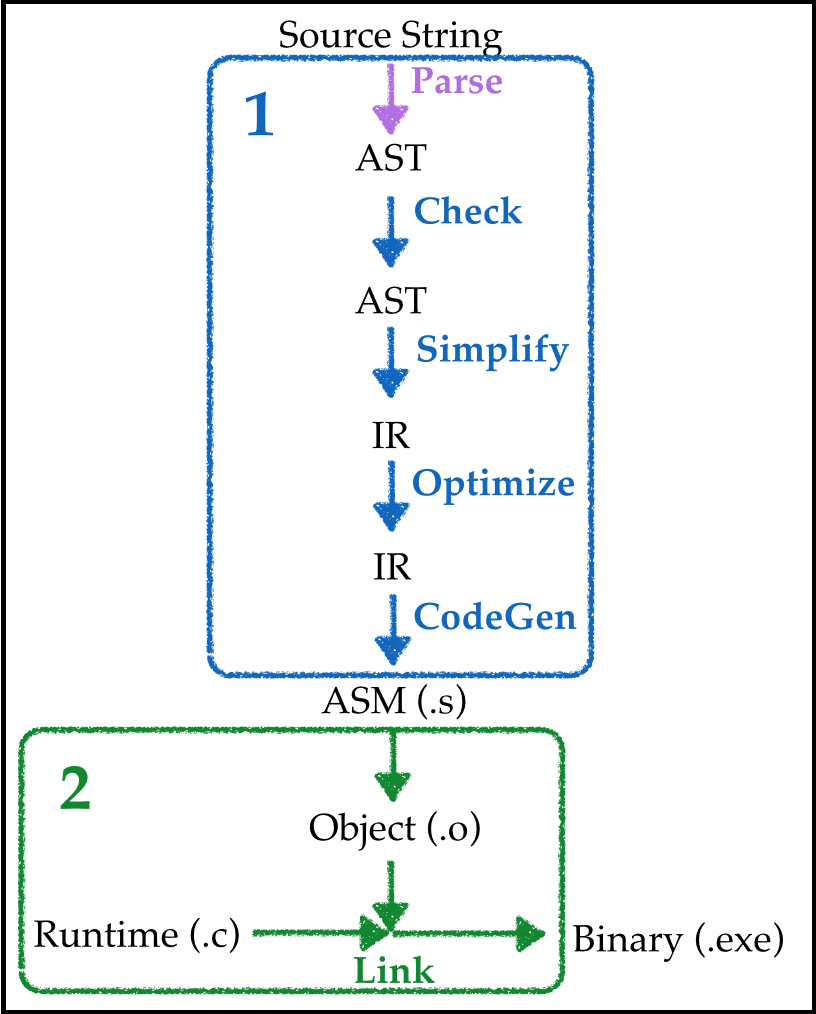

Simplified Pipeline

Goal: Compile source into executable that, when run, prints the result of evaluating the source.

Approach: Lets figure out how to write

- A compiler from the input string into assembly,

- A run-time that will let us do the printing.

Next, lets see how to do (1) and (2) using our sequence of adder languages.

Adder-1

- Numbers

- e.g.

7,12,42…

The “Run-time”

Lets work backwards and start with the run-time.

Here’s what it looks like as a C program main.c

#include <stdio.h>

extern int our_code() asm("our_code_label");

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

int result = our_code();

printf("%d\n", result);

return 0;

}main just calls our_code and prints its return value

our_code is (to be) implemented in assembly,

Starting at label

our_code_label,With the desired return value stored in register

RAXper, the

Ccalling convention

Test Systems in Isolation

Key idea in (Software) Engineering:

Decouple systems so you can test one component without (even implementing) another.

Lets test our “run-time” without even building the compiler.

Testing the Runtime: A Really Simple Example

Given a SourceProgram

42We want to compile the above into an assembly file forty_two.s that looks like:

section .text

global our_code_label

our_code_label:

mov rax, 42

retFor now, lets just

- write that file by hand, and test to ensure

- object-generation and then

- linking works

(On MacOS)

$ nasm -f macho64 -o forty_two.o forty_two.s

$ clang -g -m64 -o forty_two.run c-bits/main.c forty_two.o(On Linux)

$ nasm -f elf64 -o forty_two.o forty_two.s

$ clang -g -m64 -o forty_two.run c-bits/main.c forty_two.oWe can now run it:

$ forty_two.run

42Hooray!

The “Compiler”

Recall, that compilers were invented to avoid writing assembly by hand

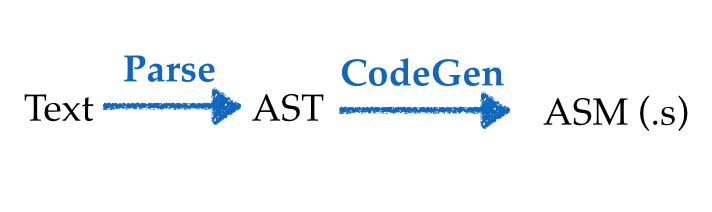

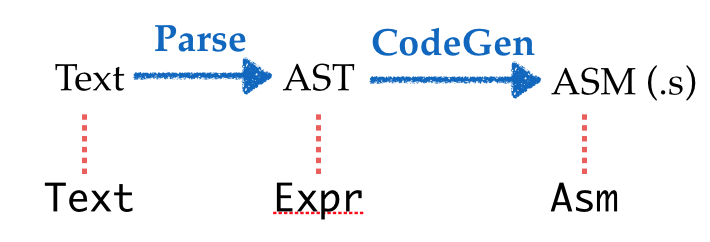

First Step: Types

To go from source to assembly, we must do:

Our first step will be to model the problem domain using types.

Lets create types that represent each intermediate value:

Textfor the raw input sourceExprfor the ASTAsmfor the output x86 assembly

Defining the Types: Text

Text is raw strings, i.e. sequences of characters

texts :: [Text]

texts =

[ "It was a dark and stormy night..."

, "I wanna hold your hand..."

, "12"

]

Defining the Types: Expr

We convert the Text into a tree-structure defined by the datatype

data Expr = Number IntNote: As we add features to our language, we will keep adding cases to Expr.

Defining the Types: Asm

Lets also do this gradually as the x86 instruction set is HUGE!

Recall, we need to represent

section .text

global our_code_label

our_code_label:

mov rax, 42

retAn Asm program is a list of instructions each of which can:

- Create a

Label, or - Move a

Arginto aRegister Returnback to the run-time.

type Asm = [Instruction]

data Instruction

= ILabel Text

| IMov Arg Arg

| IRetWhere we have

data Register

= RAX

data Arg

= Const Int -- a fixed number

| Reg Register -- a register

Second Step: Transforms

Ok, now we just need to write the functions:

parse :: Text -> Expr -- 1. Transform source-string into AST

compile :: Expr -> Asm -- 2. Transform AST into assembly

asm :: Asm -> Text -- 3. Transform assembly into output-stringPretty straightforward:

parse :: Text -> Expr

parse = parseWith expr

where

expr = integer

compile :: Expr -> Asm

compile (Number n) =

[ IMov (Reg RAX) (Const n)

, IRet

]

asm :: Asm -> Text

asm is = L.intercalate "\n" [instr i | i <- is]Where instr is a Text representation of each Instruction

instr :: Instruction -> Text

instr (IMov a1 a2) = printf "mov %s, %s" (arg a1) (arg a2)

arg :: Arg -> Text

arg (Const n) = printf "%d" n

arg (Reg r) = reg r

reg :: Register -> Text

reg RAX = "rax"

Brief digression: Type-Classes

Note that above we have four separate functions that crunch different types to the Text representation of x86 assembly:

asm :: Asm -> Text

instr :: Instruction -> Text

arg :: Arg -> Text

reg :: Register -> TextRemembering names is hard.

We can write an overloaded function, and let the compiler figure out the correct implementation from the type, using Type-Classes.

The following defines an interface for all those types a that can be converted to x86 assembly:

class ToX86 a where

asm :: a -> TextNow, to overload, we say that each of the types Asm, Instruction, Arg and Register implements or has an instance of ToX86

instance ToX86 Asm where

asm is = L.intercalate "\n" [asm i | i <- is]

instance ToX86 Instruction where

asm (IMov a1 a2) = printf "mov %s, %s" (asm a1) (asm a2)

instance ToX86 Arg where

asm (Const n) = printf "%d" n

asm (Reg r) = asm r

instance ToX86 Register where

asm RAX = "rax"Note in each case above, the compiler figures out the correct implementation, from the types…

Adder-2

Well that was easy! Lets beef up the language!

- Numbers + Increment

- e.g.

add1(7),add1(add1(12)), …

Repeat our Recipe

- Build intuition with examples,

- Model problem with types,

- Implement compiler via type-transforming-functions,

- Validate compiler via tests.

1. Examples

First, lets look at some examples.

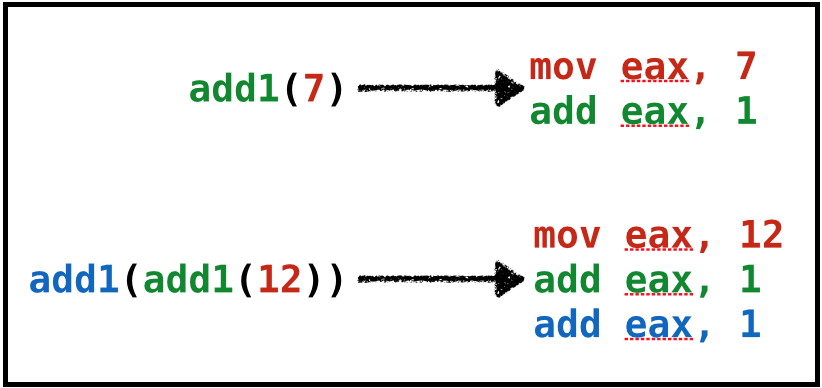

Example 1

How should we compile?

add1(7)In English

- Move

7into theraxregister - Add

1to the contents ofrax

In ASM

mov rax, 7

add rax, 1Aha, note that add is a new kind of Instruction

Example 2

How should we compile

add1(add1(12))In English

- Move

12into theraxregister - Add

1to the contents ofrax - Add

1to the contents ofrax

In ASM

mov rax, 12

add rax, 1

add rax, 1

Compositional Code Generation

Note correspondence between sub-expressions of source and assembly

We will write compiler in compositional manner

- Generating

Asmfor each sub-expression (AST subtree) independently, - Generating

Asmfor super-expression, assuming the value of sub-expression is inRAX

2. Types

Next, lets extend the types to incorporate new language features

Extend Type for Source and Assembly

Source Expressions

data Expr = ...

| Add1 ExprAssembly Instructions

data Instruction

= ...

| IAdd Arg Arg

Example-1 Revisited

src1 = "add1(7)"

exp1 = Add1 (Number 7)

asm1 = [ IMov (Reg RAX) (Const 7)

, IAdd (Reg RAX) (Const 1)

]

Example-2 Revisited

src2 = "add1(add1(12))"

exp2 = Add1 (Add1 (Number 12))

asm2 = [ IMov (Reg RAX) (Const 12)

, IAdd (Reg RAX) (Const 1)

, IAdd (Reg RAX) (Const 1)

]

3. Transforms

Now lets go back and suitably extend the transforms:

parse :: Text -> Expr -- 1. Transform source-string into AST

compile :: Expr -> Asm -- 2. Transform AST into assembly

asm :: Asm -> Text -- 3. Transform assembly into output-stringLets do the easy bits first, namely parse and asm

Parse

parse :: Text -> Expr

parse = parseWith expr

expr :: Parser Expr

expr = try primExpr

<|> integer

primExpr :: Parser Expr

primExpr = Add1 <$> rWord "add1" *> parens expr

Asm

To update asm just need to handle case for IAdd

instance ToX86 Instruction where

asm (IMov a1 a2) = printf "mov %s, %s" (asm a1) (asm a2)

asm (IAdd a1 a2) = printf "add %s, %s" (asm a1) (asm a2)Note

- GHC will tell you exactly which functions need to be extended (Types, FTW!)

- We will not discuss

parseandasmany more…

Compile

Finally, the key step is

compile :: Expr -> Asm

compile (Number n)

= [ IMov (Reg RAX) (Const n)

]

compile (Add1 e)

= compile e -- RAX holds value of result of `e` ...

++ [ IAdd (Reg RAX) (Const 1) ] -- ... so just increment it.

Examples Revisited

Lets check that compile behaves as desired:

>>> (compile (Number 12)

[ IMov (Reg RAX) (Const 12) ]

>>> compile (Add1 (Number 12))

[ IMov (Reg RAX) (Const 12)

, IAdd (Reg RAX) (Const 1)

]

>>> compile (Add1 (Add1 (Number 12)))

[ IMov (Reg RAX) (Const 12)

, IAdd (Reg RAX) (Const 1)

, IAdd (Reg RAX) (Const 1)

]

Adder-3

You do it!

- Numbers + Increment + Double

- e.g.

add1(7),twice(add1(12)),twice(twice(add1(42)))

Adder-4

- Numbers + Increment + Decrement + Local Variables

- e.g.

let x = add1(7), y = add1(x) in add1(y)

Can you think why local variables make things more interesting?

Repeat our Recipe

- Build intuition with examples,

- Model problem with types,

- Implement compiler via type-transforming-functions,

- Validate compiler via tests.

Step 1: Examples

Lets look at some examples

Example: let1

let x = 10

in

xNeed to store 1 variable – x

Example: let2

let x = 10 -- x = 10

, y = add1(x) -- y = 11

, z = add1(y) -- z = 12

in

add1(z) -- 13Need to store 3 variables– x, y, z

Example: let3

let a = 10

, c = let b = add1(a)

in

add1(b)

in

add1(c)Need to store 3 variables – a, b, c – but at most 2 at a time

- First

a, b, thena, c - Don’t need

bandcsimultaneously

Problem: Registers are Not Enough

A single register rax is useless:

- May need 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 … values.

There is only a fixed number (say, N) of registers

- And our programs may need to store more than

Nvalues, so

Need to dig for more storage space!

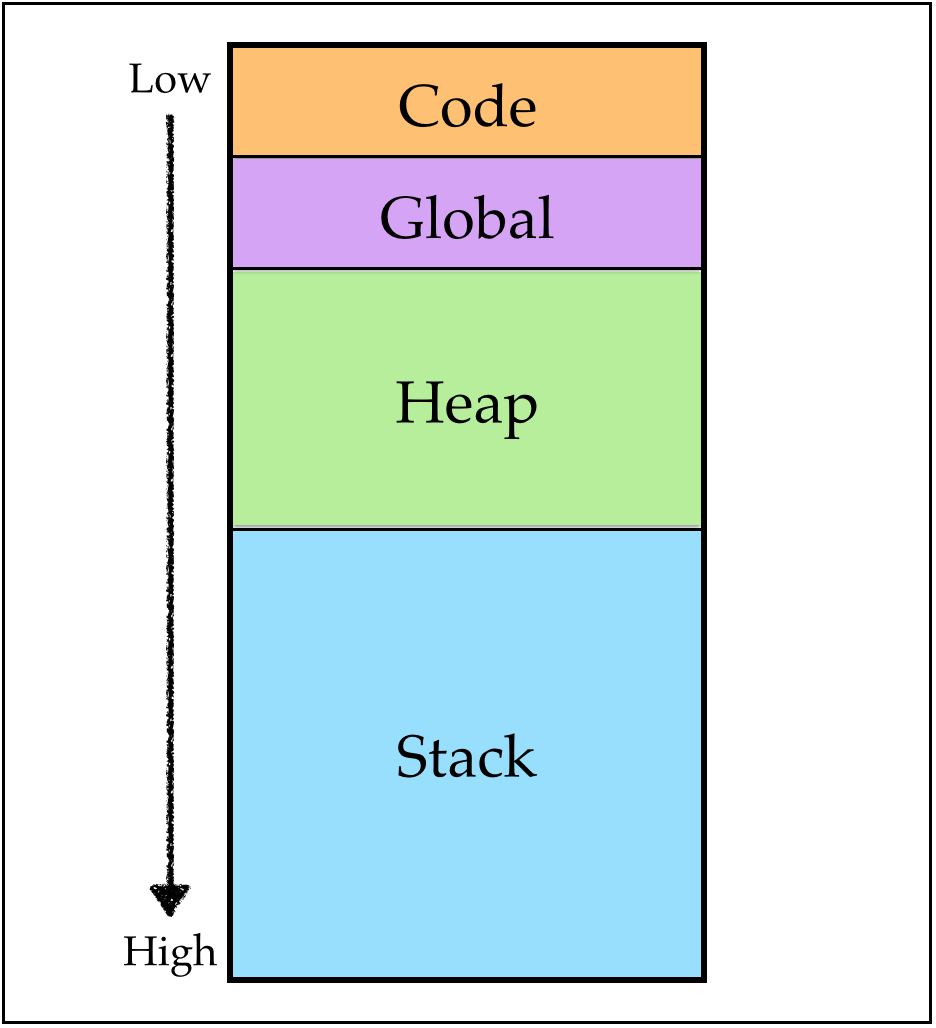

Memory: Code, Globals, Heap and Stack

Here’s what the memory – i.e. storage – looks like:

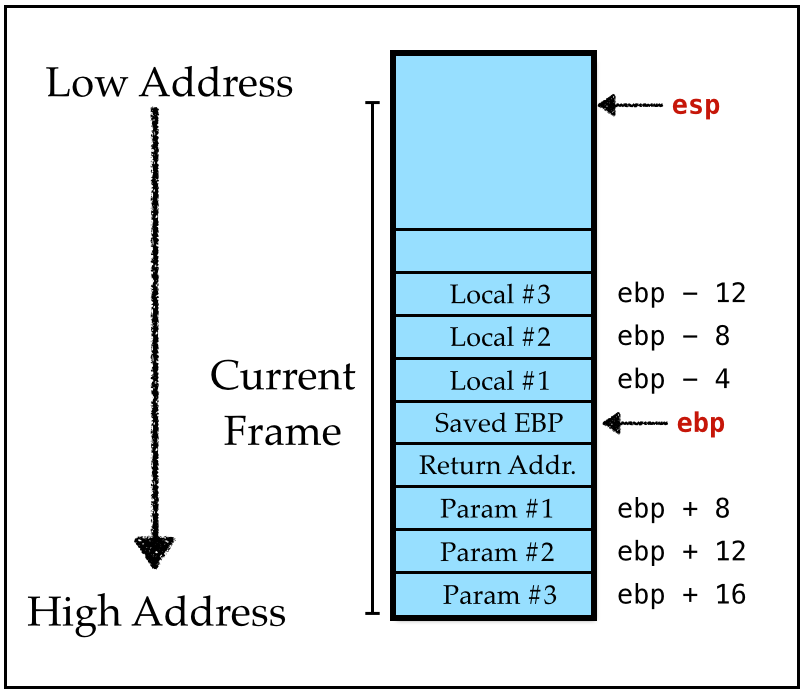

Focusing on “The Stack”

Lets zoom into the stack region, which when we start looks like this:

The stack grows downward (i.e. to smaller addresses)

We have lots of 8-byte slots on the stack at offsets from the “stack pointer” at addresses:

[RBP - 8 * 1],[RBP - 8 * 2],[RBP - 8 * 3]…,

Note: On 32-bit machines

- We’d use the

raxregister (vsraxin 64-bit) - The “base” is the

ebpregister (vsrbpin 64-bit) - Each slot is

4-bytes (vs8in 64-bit)

How to compute mapping from variables to slots ?

The i-th stack-variable lives at address [RBP - 8 * i]

Required A mapping

- From source variables (

x,y,z…) - To stack positions (

1,2,3…)

Solution The structure of the lets is stack-like too…

- Maintain an

Envthat mapsId |-> StackPosition

let x = e1 in e2 adds x |-> i to Env

- where

iis ``current’’ size of stack.

Let-bindings and Stacks: Example-1

-- []

let x = 1

in -- [ x |-> 1 ]

x

Let-bindings and Stacks: Example-2

-- []

let x = 1

-- [x |-> 1]

, y = add1(x)

-- [y |-> 2, x |-> 1]

, z = add1(y)

in -- [z |- 3, y |-> 2, x |-> 1]

add1(z)

QUIZ

At what position on the stack do we store variable c ?

let a = 1

, c =

let b = add1(a)

in add1(b)

in

add1(c)A. 1

B. 2

C. 3

D. 4

E. not on stack!

Strategy

-- ENV(n)

let x = E1

in -- [x |-> n+1, ENV(n)]

E2

-- ENV(n)

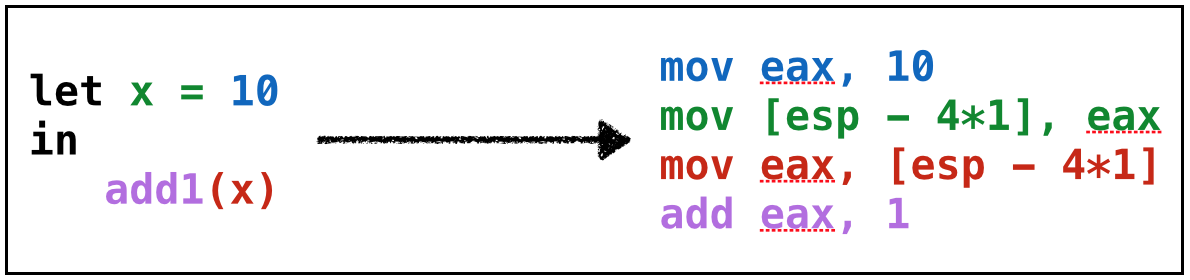

Strategy: Variable Definition

At each point, we have env that maps (previously defined) Id to StackPosition

To compile let x = e1 in e2 we

- Compile

e1usingenv(i.e. resulting value will be stored inrax) - Move

raxinto[RBP - 8 * i] - Compile

e2usingenv'

(where env' be env with x |-> i i.e. push x onto env at position i)

Strategy: Variable Use

To compile x given env

- Move

[RBP - 8 * i]intorax

(where env maps x |-> i)

Example: Let-bindings to Asm

Lets see how our strategy works by example:

Example: let1

QUIZ: let2

When we compile

let x = 10

, y = add1(x)

in

add1(y)The assembly looks like

mov rax, 10 ; LHS of let x = 10

mov [RBP - 8*1], rax ; save x on the stack

mov rax, [RBP - 8*1] ; LHS of , y = add1(x)

add rax, 1 ; ""

???

add rax, 1What .asm instructions shall we fill in for ???

mov [RBP - 8 * 1], rax ; A

mov rax, [RBP - 8 * 1]

mov [RBP - 8 * 1], rax ; B

mov [RBP - 8 * 2], rax ; C

mov [RBP - 8 * 2], rax ; D

mov rax, [RBP - 8 * 2]

; E (empty! no instructions)

Example: let3

Lets compile

let a = 10

, c = let b = add1(a)

in

add1(b)

in

add1(c)Lets figure out what the assembly looks like!

mov rax, 10 ; LHS of let a = 10

mov [RBP - 8*1], rax ; save a on the stack

???

Step 2: Types

Now, we’re ready to move to the implementation!

Source Expressions

type Id = Text

data Expr = ...

| Let Id Expr Expr -- `let x = e1 in e2` represented as `Let x e1 e2`

| Var Id -- `x` represented as `Var x`Assembly Instructions

Lets enrich the Instruction to include the register-offset [RBP - 8*i]

data Arg = ...

| RegOffset Reg Int -- `[RBP - 8*i]` modeled as `RegOffset RBP i`

Environments

An Env type to track stack-positions of variables with API

pushvariable ontoEnv(returning its position),lookupa variable’s position inEnv

push :: Id -> Env -> (Int, Env)

push x env = (i, (x, i) : env)

where

i = 1 + length env

lookup :: Id -> Env -> Maybe Int

lookup x ((y, i) : env)

| x == y = Just i

| otherwise = lookup x env

lookup x [] = Nothing

Step 3: Transforms

Almost done: just write code formalizing the above strategy

Code: Variable Use

compileEnv env (Var x) = [ IMov (Reg RAX) (RegOffset RBP i) ]

where

i = fromMaybe err (lookup x env)

err = error (printf "Error: Variable '%s' is unbound" x)

Code: Variable Definition

compileEnv env (Let x e1 e2 l) = compileEnv env e1

++ IMov (RegOffset RBP i) (Reg RAX)

: compileEnv env' e2

where

(i, env') = pushEnv x env

Step 4: Tests

Lets take our adder compiler out for a spin!

Recap: We just wrote our first Compilers

SourceProgram will be a sequence of four tiny “languages”

- Numbers

- e.g.

7,12,42…

- Numbers + Increment

- e.g.

add1(7),add1(add1(12)), …

- Numbers + Increment + Decrement

- e.g.

add1(7),add1(add1(12)),sub1(add1(42))

- Numbers + Increment + Decrement + Local Variables

- e.g.

let x = add1(7), y = add1(x) in add1(y)

Using a Recipe

- Build intuition with examples,

- Model problem with types,

- Implement compiler via type-transforming-functions,

- Validate compiler via tests.

Will iterate on this till we have a pretty kick-ass language.